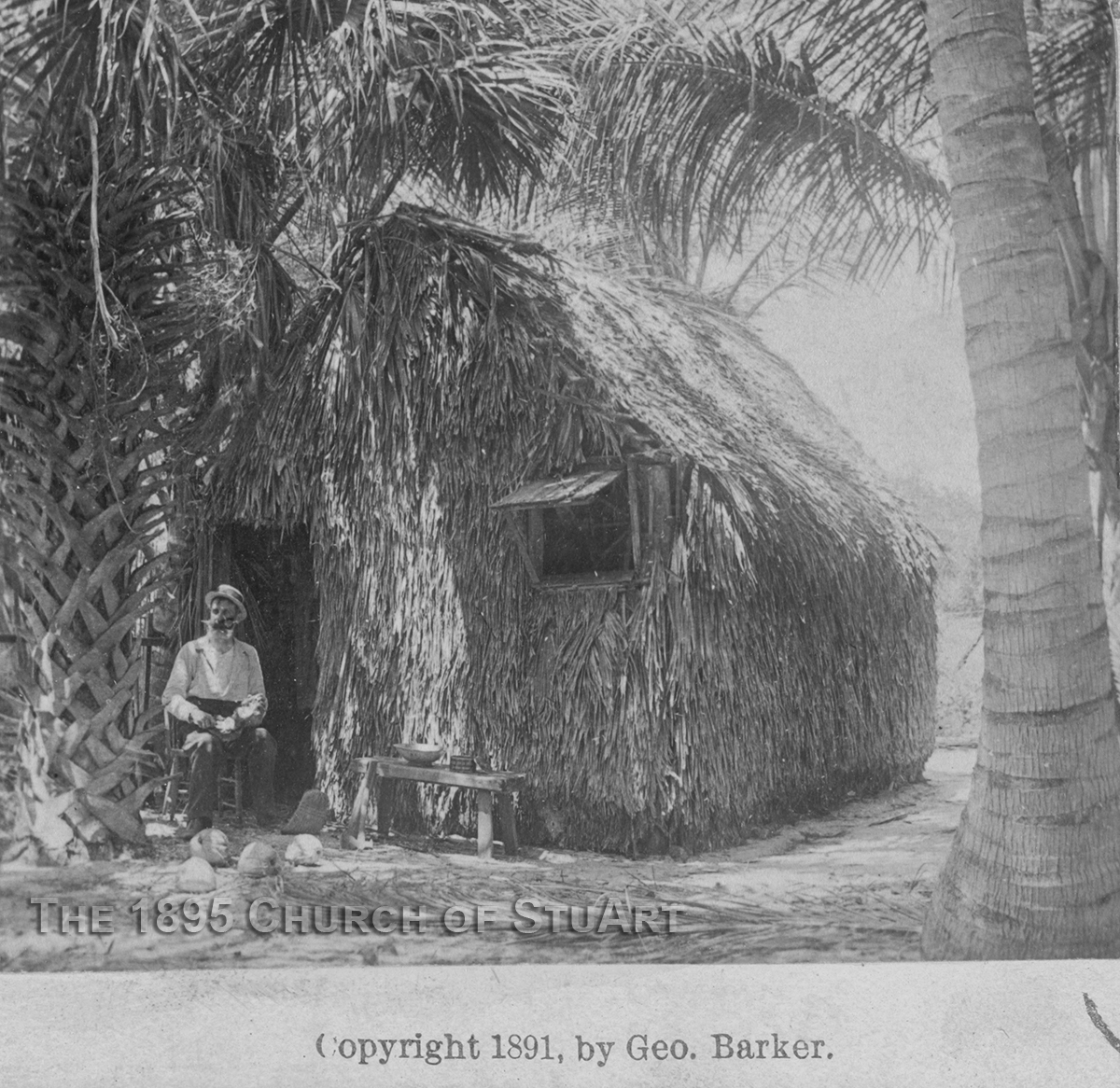

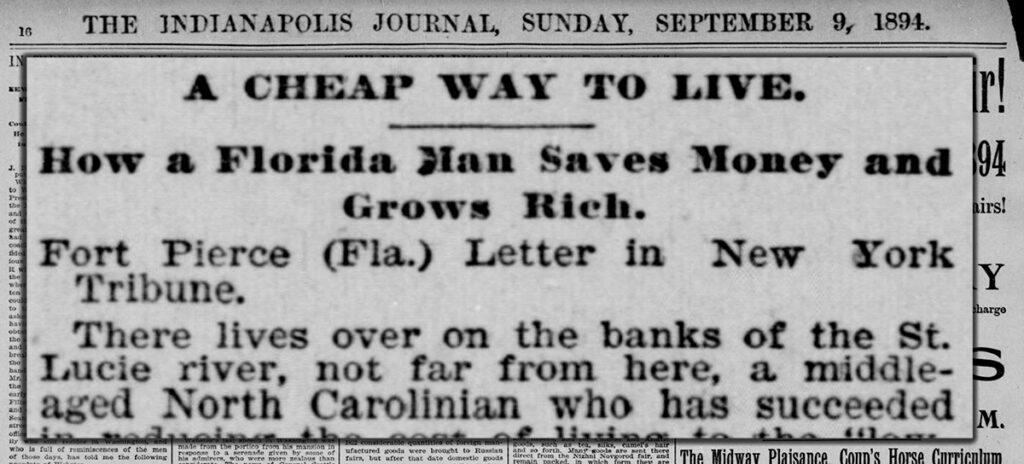

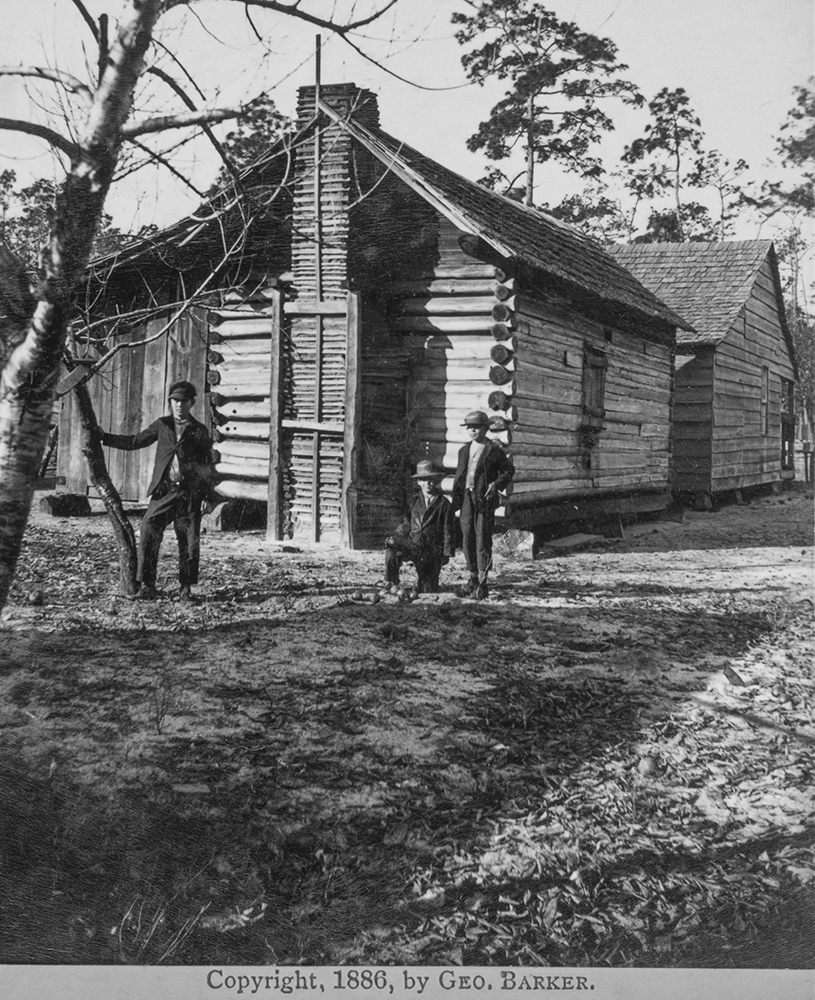

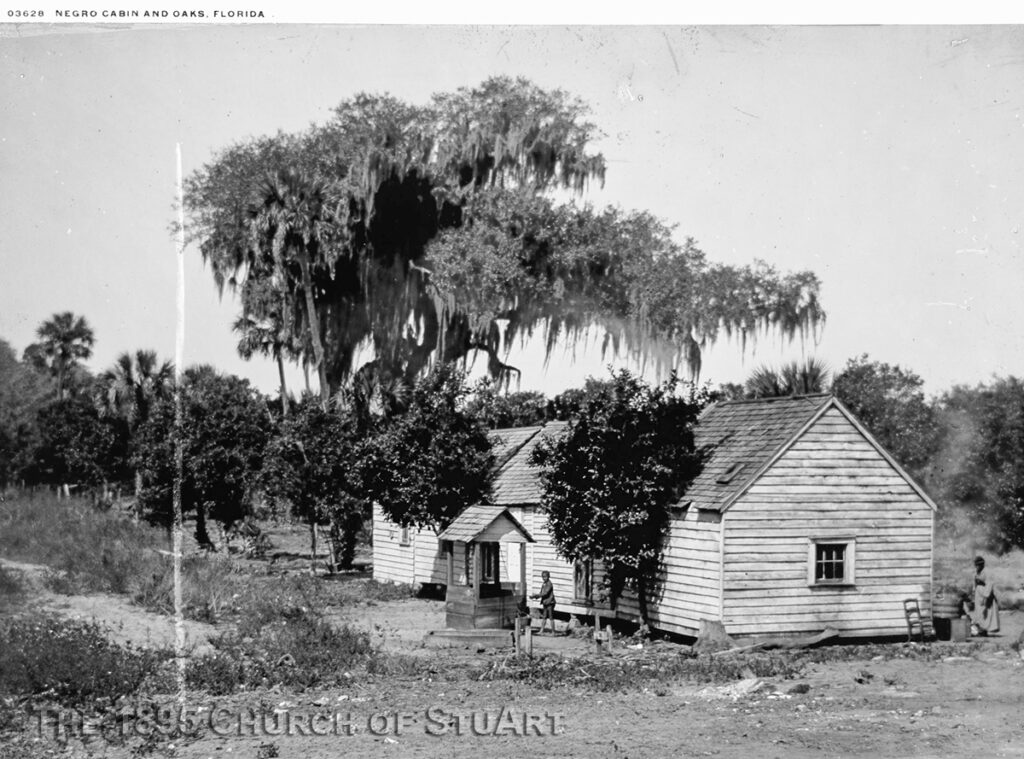

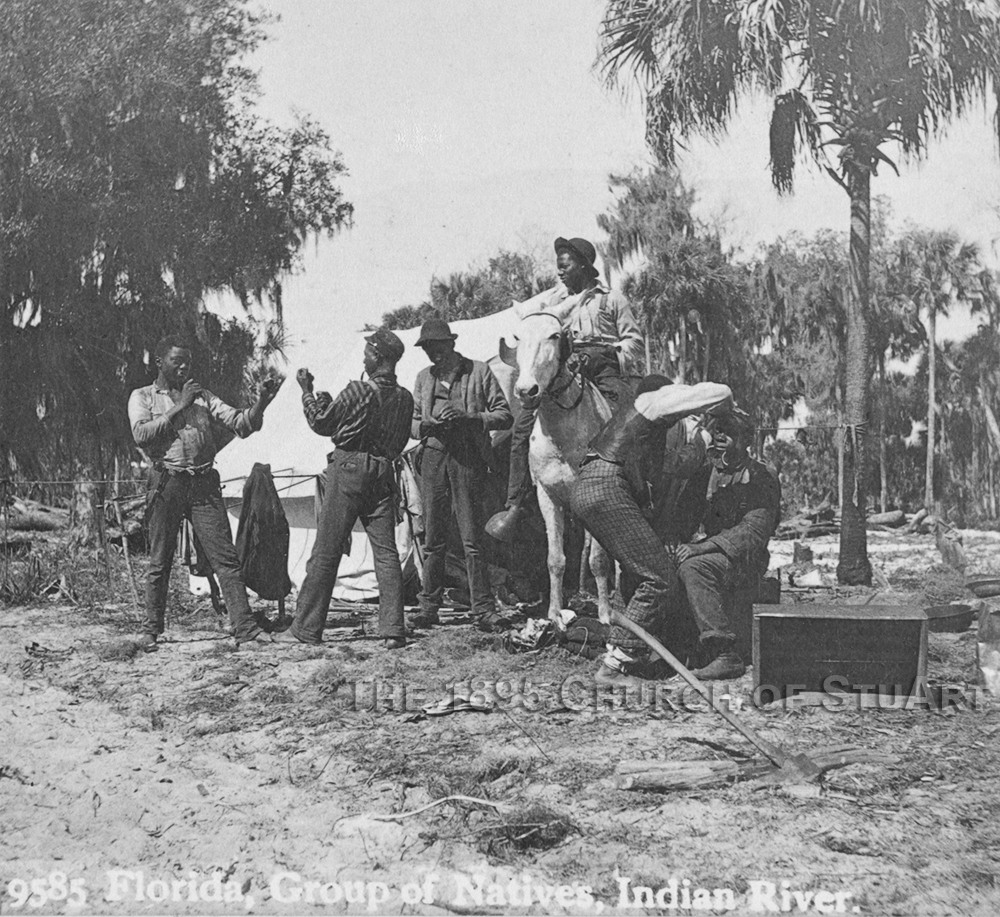

The article titled ‘A Cheap Way To Live. How a Florida Man Saves Money and Grows Rich’ was published on September 9, 1894 in The Indianapolis Journal. Several newspapers of the same year also republished it. How well business wise Bill Palmer did after the “interview” we don’t know. To this day, we could not find any followups or any additional information about him. We hope you enjoy the article and assorted photographs taken in 1880s. Unfortunately, there is not so many photographs taken in the St. Lucie River area during that period, mostly the Indian River, but the photographs we collected and the article will give you a glimpse of Florida settlers’ life between 1880 and 1897.

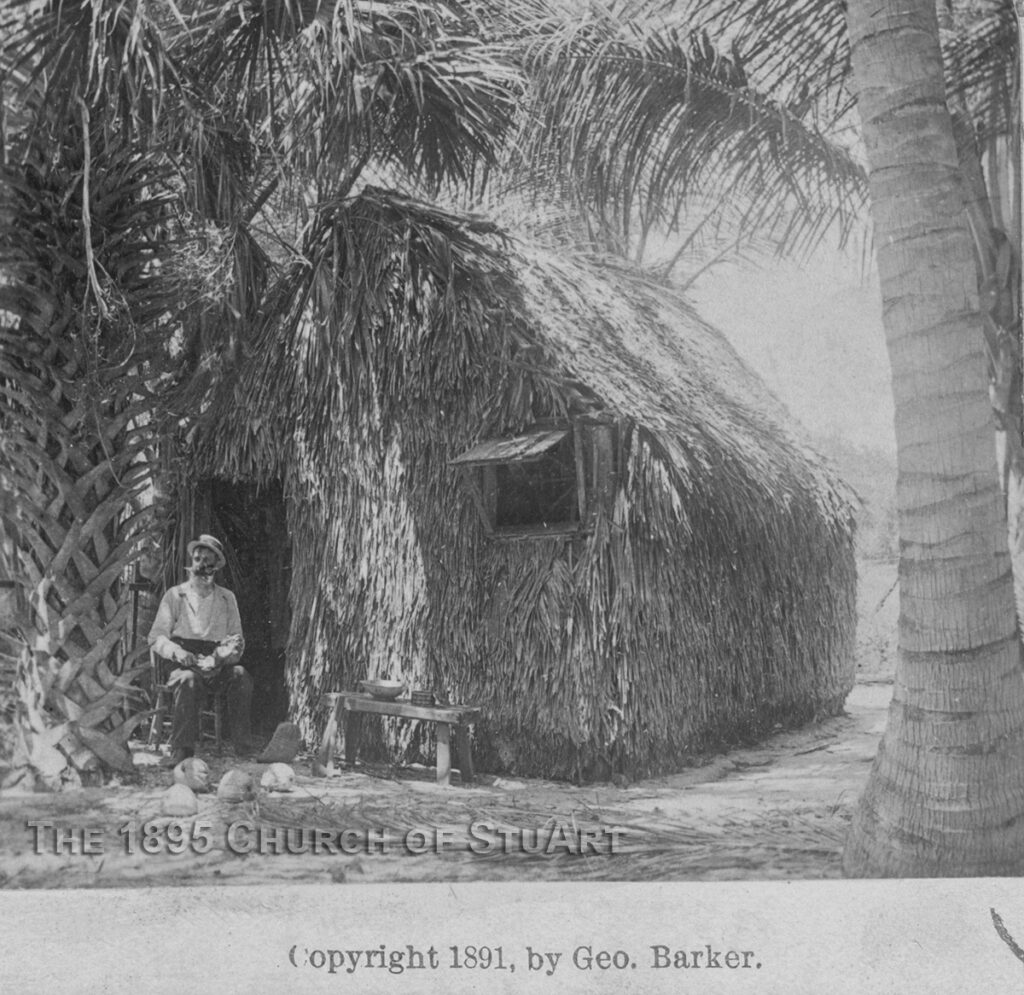

There lives over on the banks of the St. Lucie river, not far from here, a middle aged North Carolinian who has succeeded in reducing the cost of living to the “lowest common denominator,” as he himself expresses it, borrowing the phrase from his old “Greenleaf Arithmetic.” In these hard times, when economy is compulsory in nearly every walk of life, the experience of Bill Palmer Is at least interesting and it may be of some practical value to many who learn of it. The correspondent met Bill the other day on the lower deck of an Indian River steamboat. He was working his passage down the river as a deck hand. He is about forty years old, large framed and fat, too, has a jolly round face, and, withal, looks to be at peace with all the world.

“Are ye goin’ in fer locating In this country, stranger?” he began as he caught me eying him rather curiously. “If ye are, ye’ll find it the cheapes place to live in the whole United States. I’ve tried it all about in four different States and I know what I’m talking about.”

With very little encouragement in the way of questions. Bill drawled out his story. Ten years ago he was a fairly prosperous farmer in North Carolina, raising cotton, corn, potatoes, etc. But he got ambitious “res’less,” he called it and sold his farm for $3,000 cash. With this money in hand he had no family incumbrances – he bought some land near Savannah and went to truck raising. But he didn’t do much at it. One year of it was enough for Bill. Then he sold out at a sacrifice and, going to Mobile, worked as a ‘longshore-man there for a couple of years, adding a few dollars to the little pile that he had “salted.” Then he got the orange grove fever, and paid out all the money he had for some land in Volusia county, Florida. He set out a small grove, but had to resort to “trucking” again In order to get a living. His land was poor and his orange trees didn’t thrive. The place was mortgaged in order to buy fertilizers, etc., and for three years he struggled with the mortgage. Then he had a chance to sell the place for $200 more than he gave for it, took up with the offer, and a week later landed In Tampa, where he bought a fishing boat, and began the task of making a living out of the waters of Hillsborough bay. But luck was against him again, and the month of December, 1892, found him “dead broke” in Titusville.

“It was there,” said Bill, “that I ‘caught on again. I got a job working at bridge building on the East Coast line. The pay was good and the living fair. I took up a homestead of 125 acres on the St. Lucie river, not far from Sewell’s Point, and have occupied It for four months out of every year since according to the law. I have put up a comf’terble shanty, cleared twenty acres, and set them out in pineapples; and, upon my word, man, I can live there for $30 a year. What I mean is that $2.50 a month is all the cash It takes.”

Bill went on to explain that with his gun and his fishing rod he could keep his table supplied with game and fish every day in the year; he raises his own potatoes and grows his own cane for syrup; he works for the fruit growers during the picking season, and so gets all the fruit he wants free; his land also produces corn, cabbages, tomatoes, cucumbers and other “truck” in their season, and berries and small fruit grow wild in great abundance. Two suits of jeans will do for a whole year, with only one hat and one pair of shoes-underclothes and socks not coming into the calculation at all; a little money has to go for hog meat and flour occasionally, and for coffee regularly, and all the rest is for tobacco.

“Next summer,” concluded Bill. “I shall have a crop of pines that ought to bring me in at least $3,000 ‘cash money,’ and then I shall be just where I was when I left Carolina in 1884 – only I shall have a 125-acre homestead beside, and the whole thing acquired In less than three years. Living the way I do, I ought to be worth $50,000 Inside of five years. Then I’ll be willing to quit. But Just think of it, stranger, how I knocked about for eight years and had to ‘go broke’ before I struck this yere East Coast country, where an industrious man can earn from $3,000 to $3,500 a year easily by raising pineapples, and live on $30.”

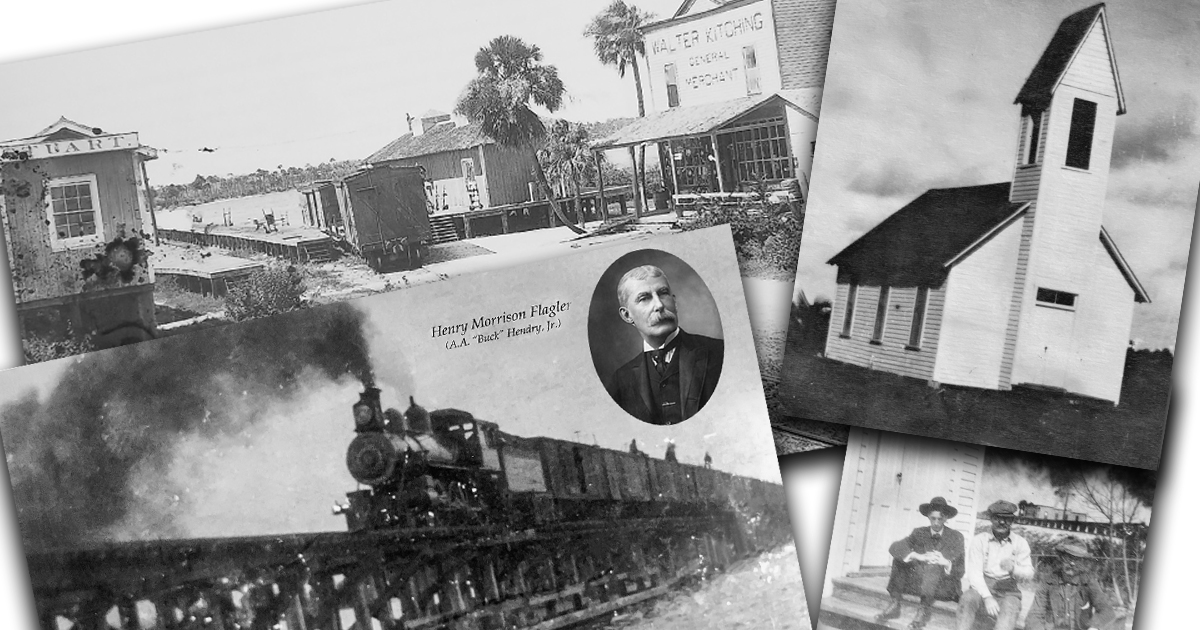

The earliest pineapple cultivation in Florida started in Key West in the 1860s. As demand for the fruit increased during the 1880s and 1890s, pineapple fever had taken hold. Farmers were eager to turn the sandy soil into profitable fruit. Plantations from 1 to over 100 acres sprouted up and down the sandy ridge of the Indian River, the St. Lucie River, and across the state.

By 1899, the industry had expanded rapidly, thanks in part to the southward extension of the Florida East Coast Railway. The railroads had an enormous impact on the growth of the market. Pineapple farmers now had the means to reach markets like Chicago in three days and New York in two days. Everyone was making money. The early 1900s produced close to one million crates a year. Florida had become the Pineapple Capital of the World.

However, the “pines” market flourished for only a brief time in Florida’s history: the brutal winters with severe freeze; the competition (by 1908, Cuba had surpassed Florida); the pineapple blight (A disease caused by mealybugs and nematodes); the Florida real estate boom when the Florida land grab began, and in 1912, many pineapple farmers began to sell off their farms to real estate speculators.

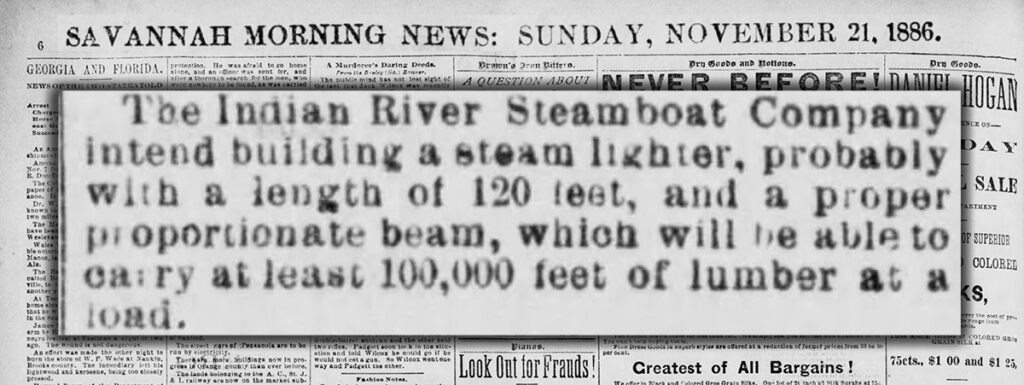

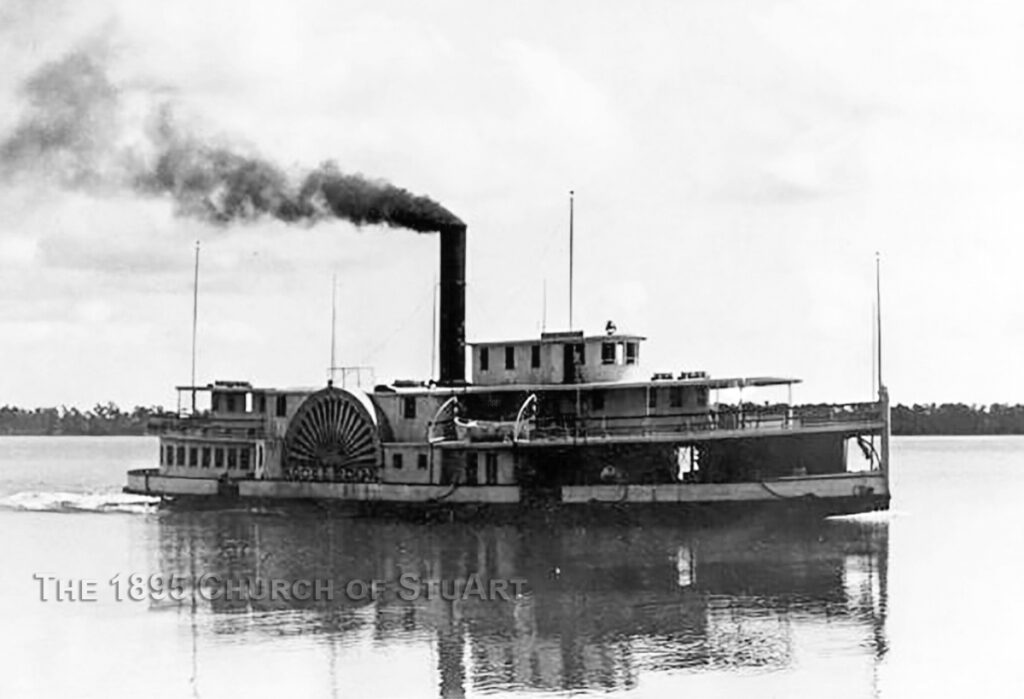

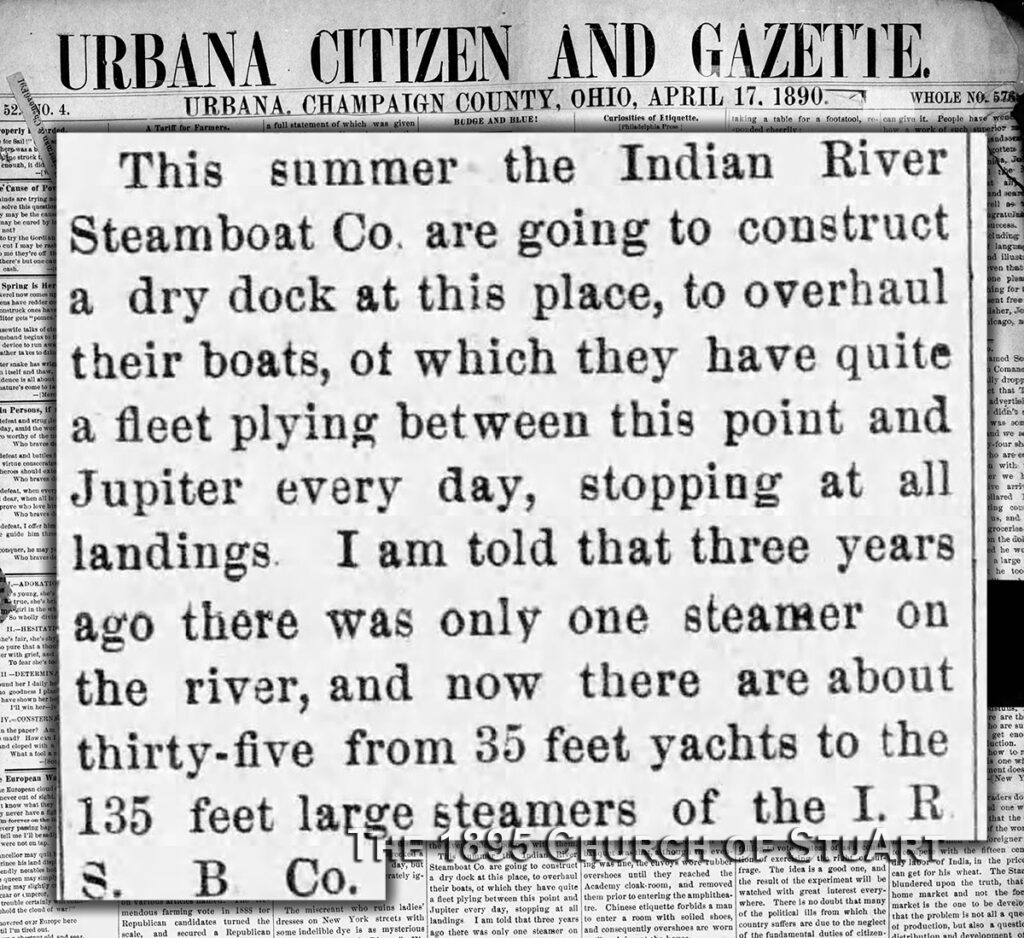

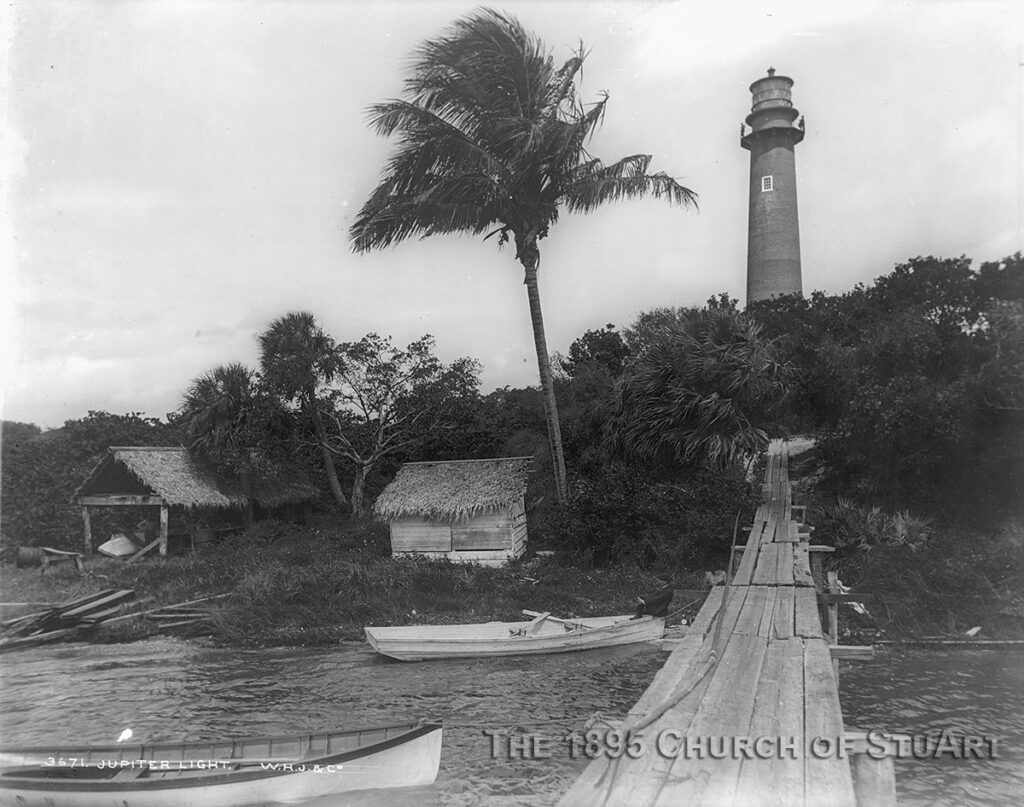

The “golden age” of steamboating on the Indian River was relatively brief, roughly from 1880 to 1900. Various sternwheel steamers carried passengers and trade goods south, and took processed fish, pineapples and other products north to market. By the late 1880s, the Indian River Steamboat Co. made regular trips with its steamer George M. White, a combination passenger and freight boat.

The company added a larger boat, the Georgiana. An even larger sidewheeler, the Rockledge, soon followed.

“Sometime in 1889 a new queen began her reign on the river under the Indian River Steamboat Company banner. She was the St. Lucie. The vessel was built in Wilmington, Del. at a cost of $30,000 and sailed under the command of Capt. Steve A. Bravo. She had 14 staterooms and a large hurricane deck and she could travel 10.5 knots over the water. The vessel drew only 35 inches of water and was able to travel almost anywhere in the Indian River lagoon. St. Lucie was 122 feet long and had a beam of 24 feet.” (“When Steamboats Reigned in Florida” book by Bob Bass, 2008) Bass also quoted Jacksonville Times-Union newspaper describing the new St. Lucie: “She is built on the same plan as many Ohio River steamers, having three decks. She is a sternwheel vessel propelled by two high pressure engines situated aft on the main deck. The forward part of this deck is occupied by the boiler and freight is stowed between. By a flight of stairs the saloon is reached; the cabin extending almost the whole length of the boat. The forward and after parts of the cabin are pleasant staterooms, comfortably fitted with easy chairs and settees of rattan, and antique oak card tables. … The staterooms are 6×6 and very comfortably fitted up. Each contains two berths with woven wire springs, and soft, comfortable mattresses and pillows. The ceilings of the decks are lines with life preservers.” A dining service was provided for passengers.

By April of 1890, there were thirty-five from 35 feet yachts to 135 feet steamers of the Indian River Steamboat Company.

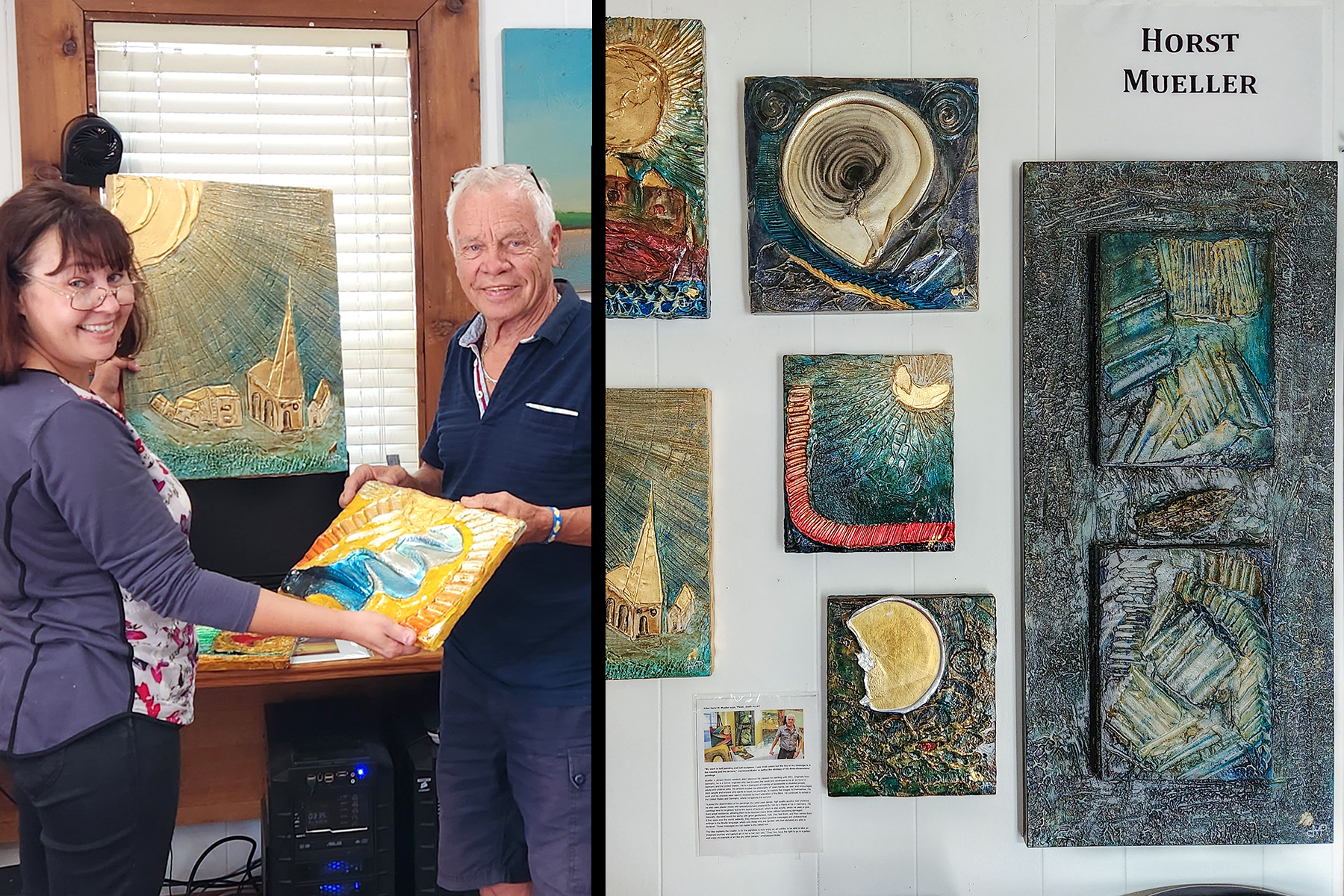

The 1895 Church of StuArt is a historical building of the first community church, also known as the Pioneer Church (the oldest church building in Martin County), built in Stuart in 1895! Your donations help us maintain, restore, and preserve the building, and also continue our research and share historical information and articles. We greatly appreciate your support! The donations are not tax deductible.