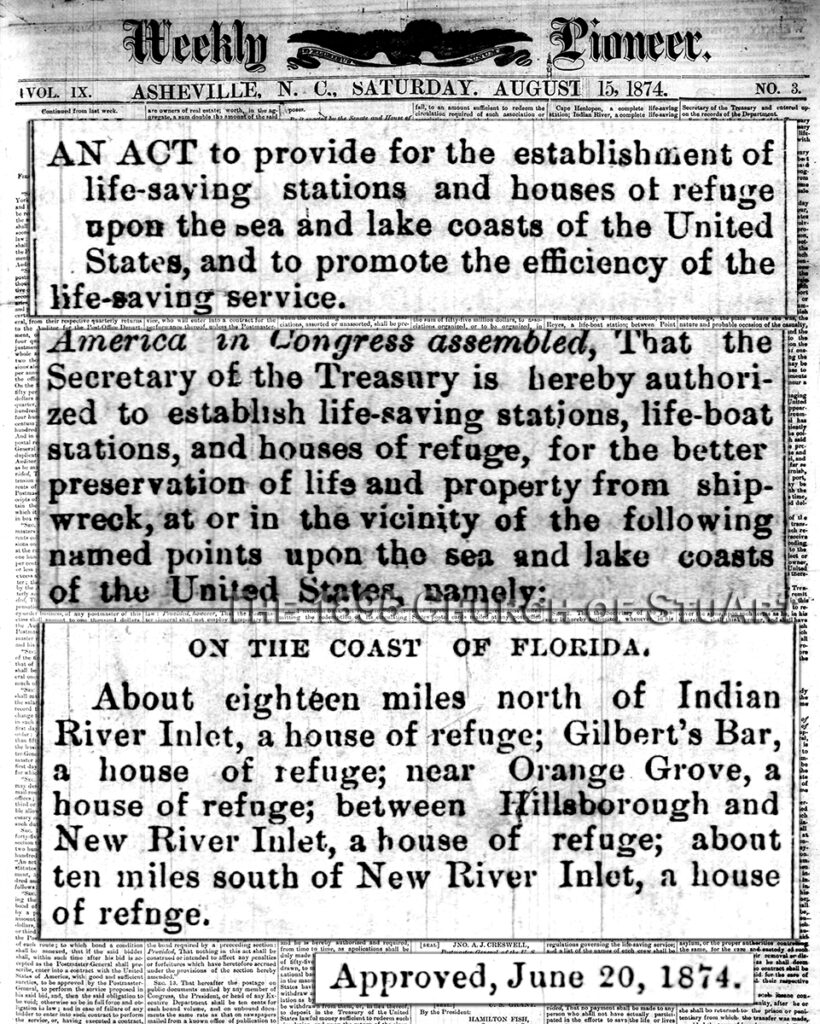

In 1874, the newspapers published “An Act to provide for the establishment of life-saving stations and houses of refuge upon the sea and lake coasts of the United States, and promote the efficiency of the life-saving services.” The act included five houses of refuge on the coast of Florida and one of them was a house of refuge at Gilbert’s Bar.

Stormy weather and jagged reefs made the Atlantic Coast of Florida a dangerous place for sailors in the 1800s. Sailors who survived the shipwrecks were stranded on beached where there were no other people to take care of them or give them food.

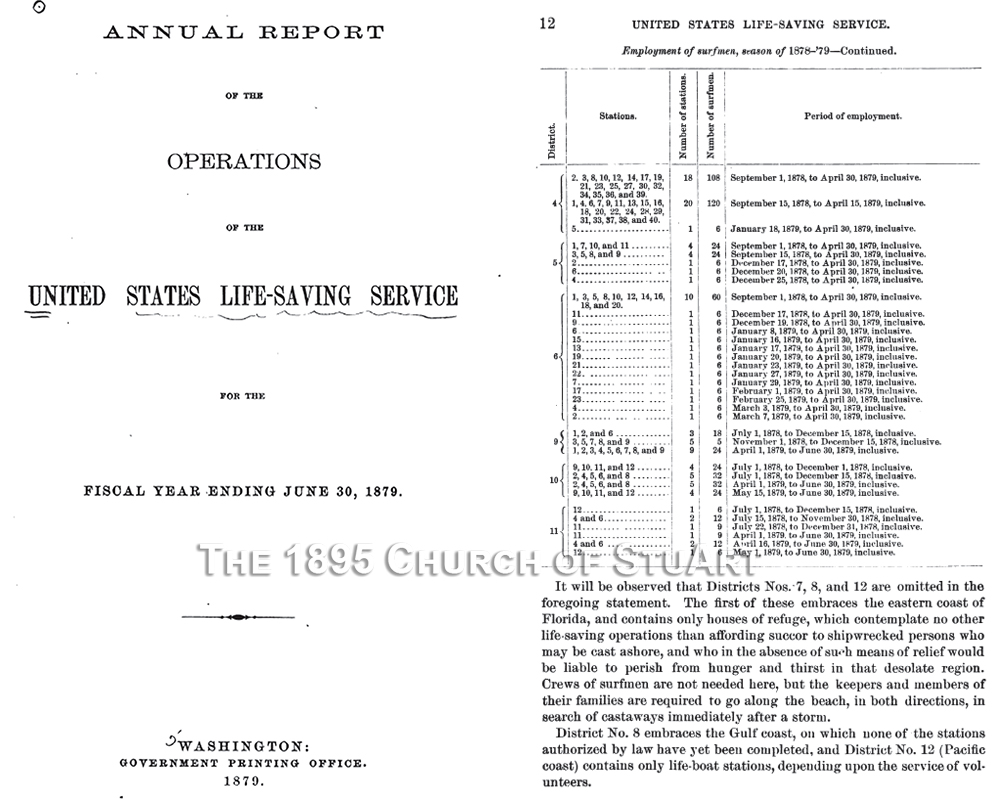

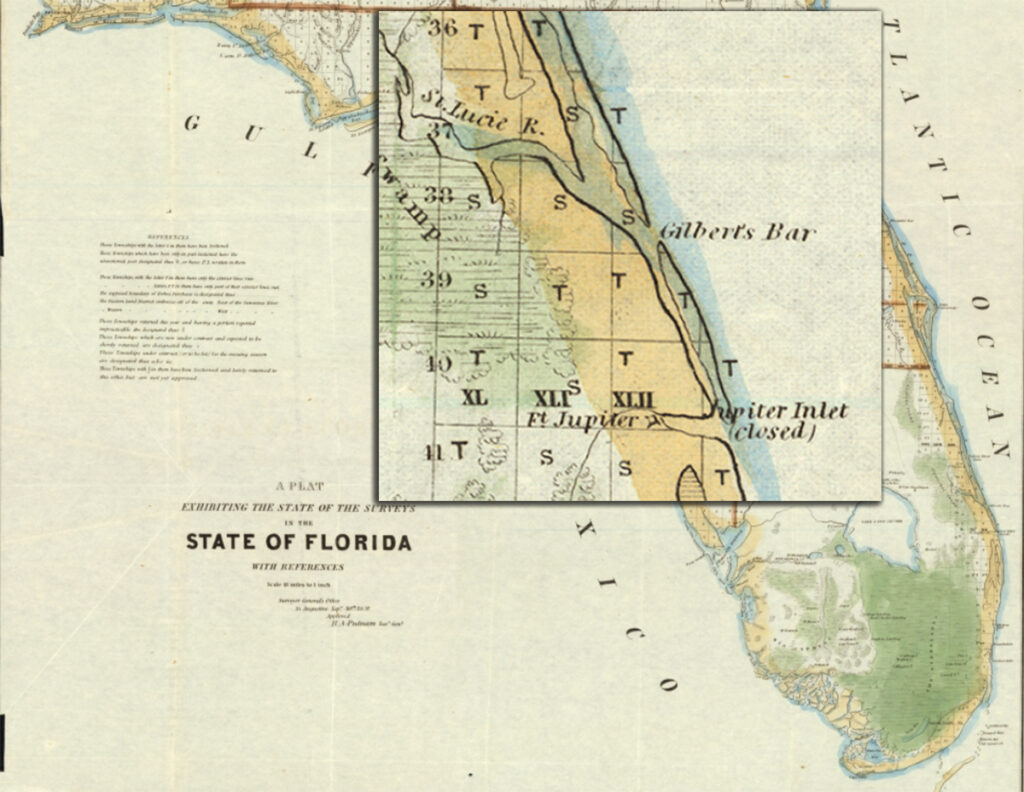

On March 19, 1875, the Secretary of the Treasury leased from William H. Hunt of Dade County, Fla., for a period of 20 years a piece of land : “in the County of Dade and State of Florida, at a place known as St. Lucie Rocks and about 1 mile north of a point known and designated as Gilbert’s Bar on the sea coast” as a site for a house of refuge. The consideration was one dollar.” The plot of ground was described as follows: “Beginning for the same at a stake set in the grounds at high water mark upon the ocean beach and running thence northerly along the beach 150 feet to a stake; thence due west about 300 feet to Indian River; thence along the bank or water’s edge southerly to a point on the river due west and about 150 feet more or less from the stake first above mentioned. Said land begin situated upon section one of Hutchinson’s Island in Township 38 S Range 39 East.” According to the 1879 “Annual Report of the Life Saving Service” these houses of refuge along the east coast of Florida “contemplate no other life saving operations than affording succor to shipwrecked persons who may be cast ashore, and who, in the absence of such means of relief, would be liable to perish from hunger and thirst in that desolate region. Crews of surfmen are not needed here, but the keepers and members of their families are required to go along the beach, in both directions, in search of castaways immediately after a storm.”

A daily journal or log was kept by the keeper and his family. The log recorded a variety of information including: conditions of the surf; the direction and force of wind and weather at midnight, sunrise, noon and sunset; barometer and thermometer readings at midnight, sunrise, noon and sunset; records of who patrolled the beaches, how far they walked and for how long; conditions about the house being clean and in good repair, any absences by the crew and for how long and who was the substitute; and how many vessels passed by and what type they were (ships, barks, brigs, schooners, steamers, sloops) and finally an area for general remarks (USLSS 1903a). Each week a transcript of the log was sent to the district superintendent who would forward it to the general superintendent. After a wreck, the keeper assembled a wreck report outlining the details of the incident and his actions (Kimball 1894:12). In the early 1880s, in addition to their usual duties of observation, record keeping and maintenance, keepers were instructed to preserve strange specimens of fish and marine curiosities for the Smithsonian Institution. Many of the keepers and their families were quite resourceful and entrepreneurial and managed to make a decent living combining pay from the government and from side businesses. Throughout the Life-Saving Service era, keepers supplemented their government paychecks with other activities such as beekeeping, boat building and farming. Several keepers provided lodging to others outside the realm of their lifesaving duties.

On April 19, 1886, the brigantine J.H. Lane, 371 tons, of Seaport, Maine, bound from Matanzas to Philadelphia with eight crewmembers and a cargo of molasses valued at $13,640 was wrecked 14.5 miles north of Jupiter lighthouse and 5.5 miles south-southwest of Gilbert’s Bar Station. The life-savers rescued seven crewmen, one life was lost, that of Henry Whitlock, steward of Portland, Maine.

On October 16, 1904, the 767 ton bark George Valentine from Camagoli, Italy, was stranded with a crew of 12. Five of the crew were lost and seven saved. On the very next day, the Spanish ship Cosme Colzado was stranded about 300 yards offshore and one sailor, Juan Money Mallona died because he was tangled in the rigging and drowned, according to eye-witnesses.

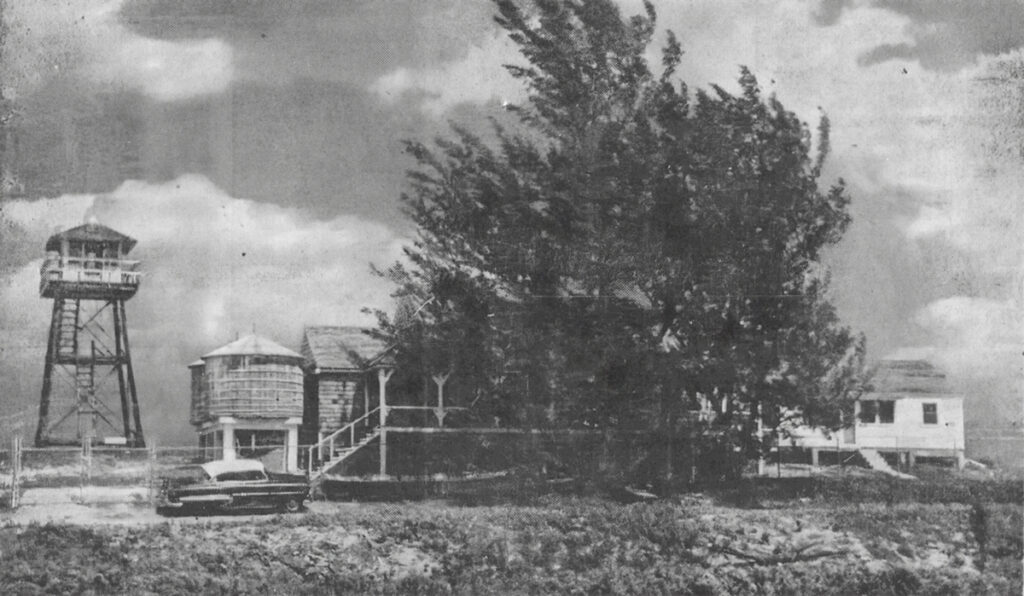

Storms and erosion can compromise the very foundations of structures built on the sand dunes. For example, in 1935 the Gilbert’s Bar House had to be moved 30 – 40ft away from the beach edge due to erosion and movement of the barrier island (Matheson 1996). The station continued in active service under the Coast Guard until 1941 when the Navy started governing it as a patrol station for the beach. Following its decommission as a Coast Guard station in 1941, the United States Navy took over Gilbert’s Bar just months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although still operated by Coast Guard personnel, Gilbert’s Bar became a valuable patrol station for the Navy and was used to protect the area from U-boats and hostile aircraft during World War II. The wooden tower, which still stands today, was built by the Navy to observe German ships offshore. Coast Guardsmen worked alongside the U.S. Navy to man the watchtower and conduct patrols of the beach. Bernard Hodapp remained at Gilbert’s Bar during World War II and received orders in April 1945 to completely decommission the station and lower the U. S. Flag. The station was closed entirely.

Keepers:

Frederick Whitehead was appointed keeper on 1 DEC 1876 and left in 1877.

P. A. McMillan was appointed keeper on 26 MAY 1880 and transferred to Station Indian River on 16 DEC 1881.

David Brown was appointed keeper on 16 DEC 1881 and resigned on 25 MAR 1885.

Samuel F. Buncker was appointed keeper on 25 MAR 1885 and resigned on 11 JUL 1888.

David McClardy was appointed keeper on 11 JUN 1888 and resigned on 2 MAY 1890.

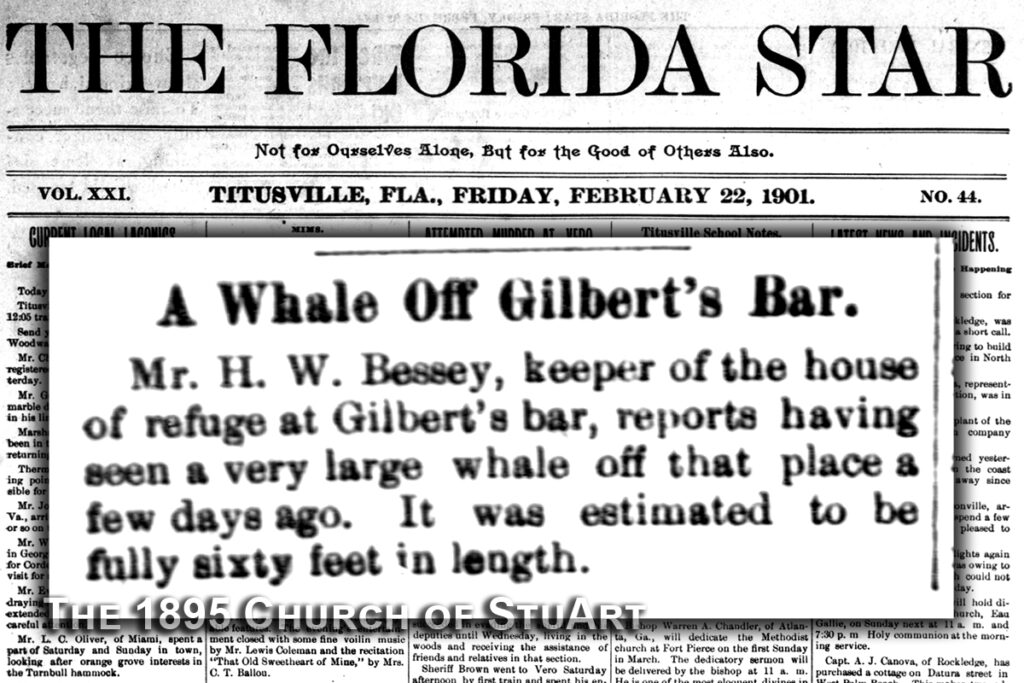

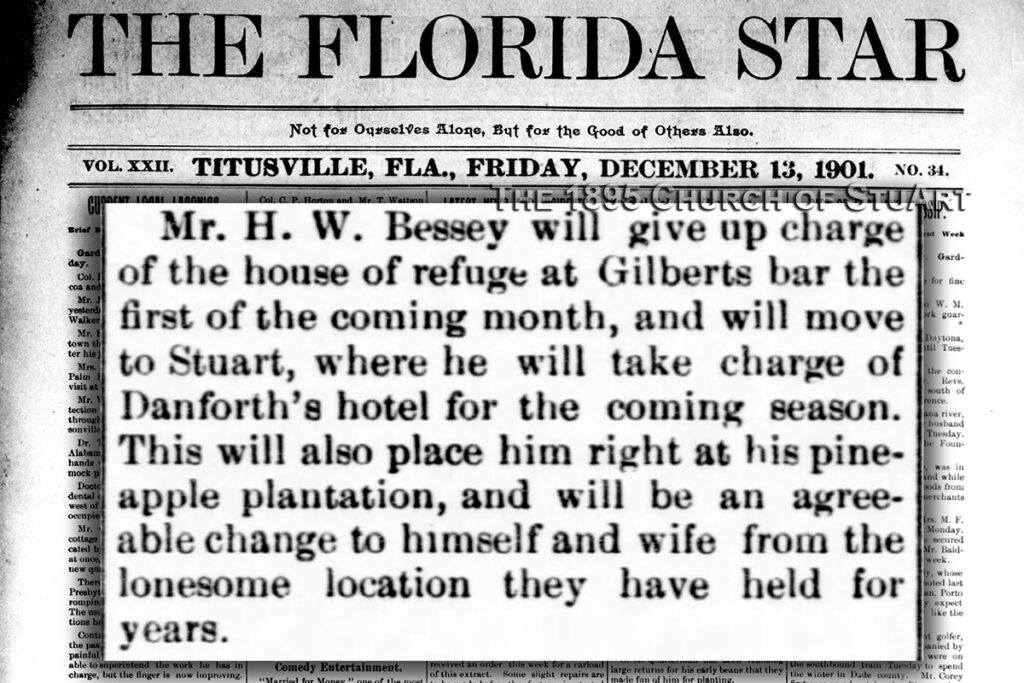

Hubert W. Bessey was appointed keeper on 12 JUL 1890 and resigned on 1 JAN 1902.

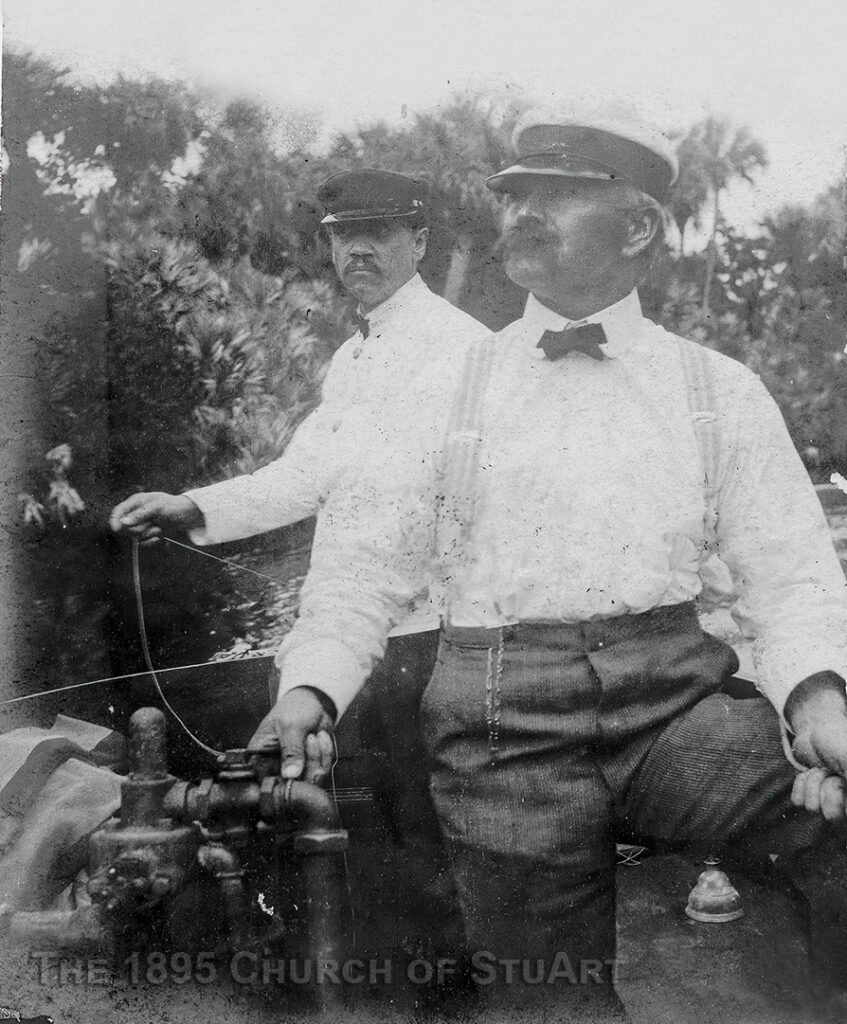

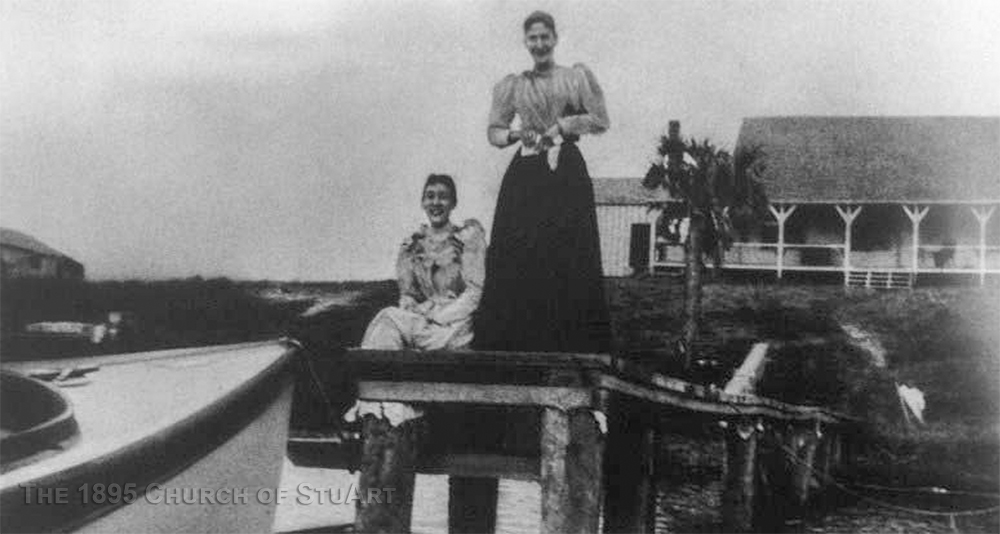

Hubert Bessey, born Dec. 17, 1855 in Medina County, Ohio, came with his brother, Willis, to South Florida in the early 1880s. Bessey, considered the first permanent resident of what would be Stuart. Hubert and Willis built a small wooden one-room ‘house’ about 1882 on the St. Lucie River (Bessey Point). Hubert would grow pineapples on the homesteaded acreage and was a skilled boat builder. He built many cat-rigged and sloop-rigged watercraft for the houses of refuge and local settlers for use on the inland waterways. The vessel in the photograph below appears to be the Mosquito Lagoon boat built by Bessey based on historical documents and other photographs. He accepted a position as keeper of the House of Refuge on remote Hutchinson Island, July 12, 1890, employed by the U.S. Government for $600 a year. Willis returned to Ohio in 1894, due to poor health. That year, Hubert had opportunity to meet Susan Ellis Corbin, a temporary visiting teacher from Tennessee. Susan was born July 25, 1868 in Alabama, but lived in Nashville, where Hubert would travel to marry the young woman, February 19, 1895. After the wedding the newlyweds returned to the house of refuge soon after.

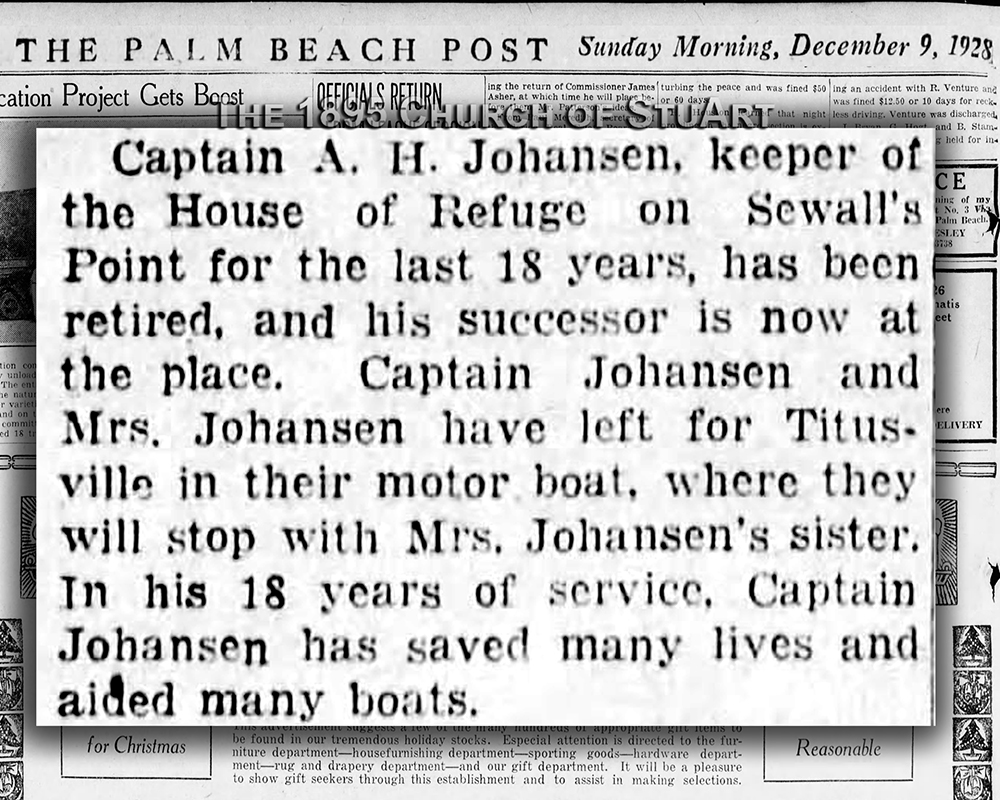

Axel H. Johansen was appointed keeper on 28 DEC 1901 and transferred to Station Biscayne Bay on 14 JAN 1903.

William E. Rea was appointed keeper on 2 JAN 1903 and resigned on 20 MAY 1907.

John H. Fromberger was appointed keeper on 2 MAY 1907 and transferred to Station Sullivan’s Island on 15 APR 1910.

Axel H. Johansen was appointed keeper on 4 MAY 1910 and served until 22 NOV 1918.

A house of refuge love story.

Axel Johansen found the love of his life, Kate Quarterman. During the late 1880s in a hurricane, Johansen’s ship wrecked offshore and for five days he floated on a piece of ship debris. When he finally washed ashore he was too tired and hurt to walk the beach so he buried himself in the sand for warmth. The next day he was discovered by two daughters of the Chester Shoals House of Refuge keeper who raced to get their father and helped the man back to the station. When he recovered, he retuned to Norway but never forgot his experience on the Florida coast. Eventually Johansen returned to Florida and made his way to the Chester Shoals House where he stayed as a guest with the keeper and family and married the Keeper’s oldest daughter, one of his rescuers. An opening for keeper at Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge became available and Axel and his wife took the position.

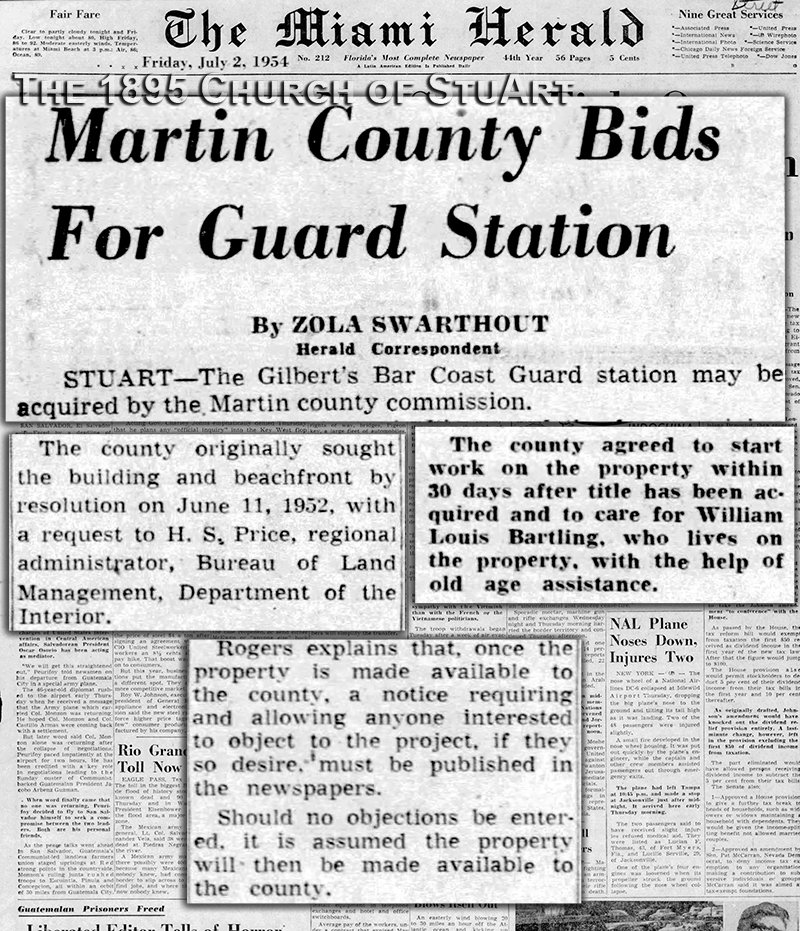

William (Louis) Bartling, unofficial and unpaid watchman of the Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge

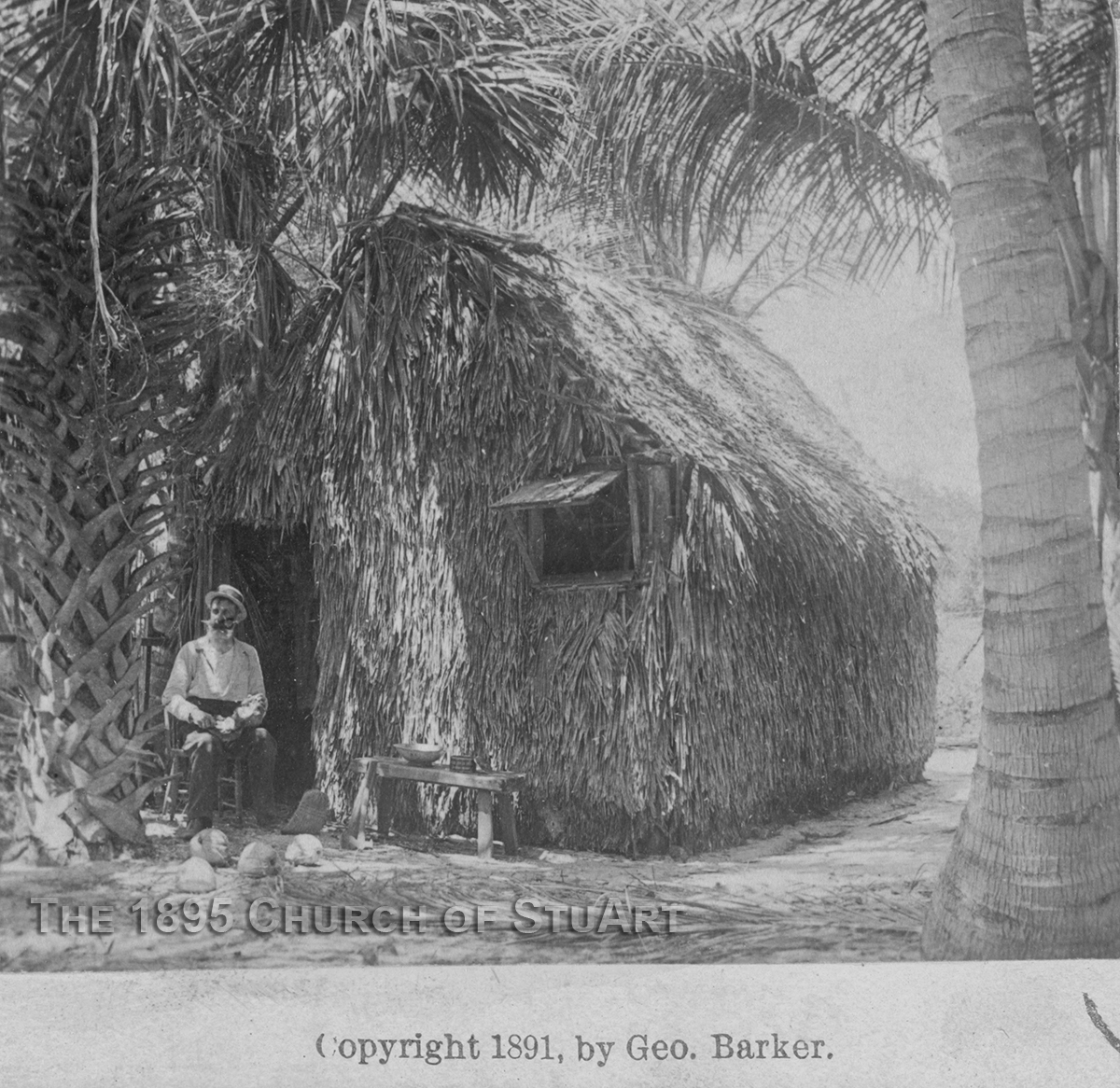

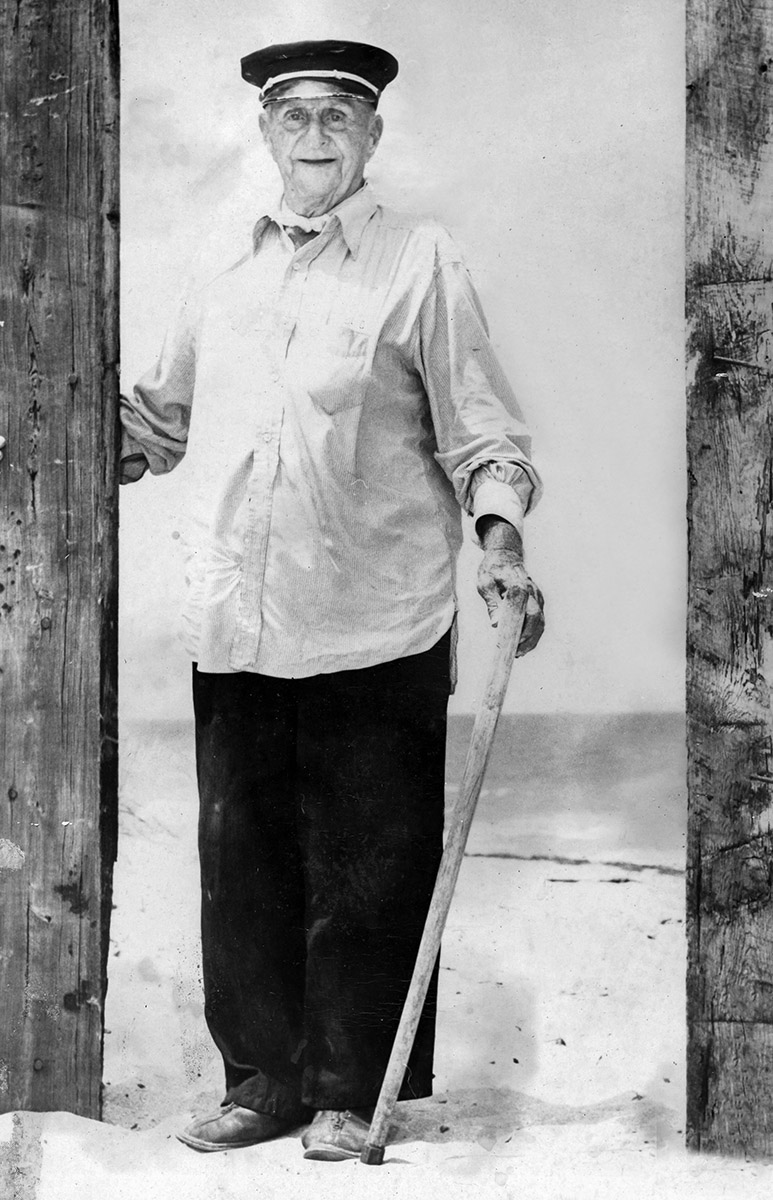

Bartling, a sailor born aboard his father’s ship in Bremerhaven in 1867, floated ashore there in 1902 on a log from the wreck of a schooner. His three companions returned to the sea, but he lived a beachcomber’s existence at Gilbert’s Bar from that day. He had a houseboat there and created a makeshift shack, which even included a kitchen, from old ship’s parts collected on the beach. His vigilance, in periods when the station was not manned, saved if from vandals. In the first war, Martin County residents tried to have him evicted as an enemy alien. Bartling journeyed to Washington and stopped that. He was already a naturalized citizen. Later, the Coast Guard sought to evict him as a squatter, only to find that they had suffered him to live there so long without protest that the government had forfeited its rights.

When the government gave the House of refuge to the Martin County Historical Society, it specified the Bartling should be allowed to live out his life on the reservation. The evening of Wednesday, Nov 19, 1958, a fire started due to an explosion in Bartling’s cooking stove as a meal was prepared. The fire was spotted by Indian River bridge toll-taker Charles Gaye and a resident of Hutchinson Island, Clarance Doege, who both called the county sheriff’s office. About 50 firefighters managed to get the blaze under control before it spread to surrounding shrubbery. Bartling’s body was located in the hot ashes of the kitchen. Bartling’s remains were buried at All Saints Cemetery in Jensen Beach and the property at Hutchinson Island on which he lived reverted back to the House of Refuge Museum.

William Louis Bartling (1867-1958) at a party for his 91st birthday at the Sandpiper Restaurant in Jensen Beach

The photo of Capt. William Louis Bartling of Hutchinson Island. Elliot Museum, Historical Society of Martin County Collection.

Between 1875 and 1886, ten houses of refuge and a life-saving station were built at intervals along Florida’s east coast below St. Augustine.

Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge in Stuart, on Hutchinson Island, is the only one still standing. It’s on the National Register of Historic Places and is preserved as a museum.

In 2008, Sandra Henderson Thurlow and Deanna Wintercorn Thurlow produced a popular publication on the Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge. This book is available at the following locations: Elliott Museum, Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge Museum, Stuart Heritage Museum, Barnes & Noble, Thurlow & Thurlow, P.A., and for those who don’t live locally – Amazon.com.

Hutchinson Island1

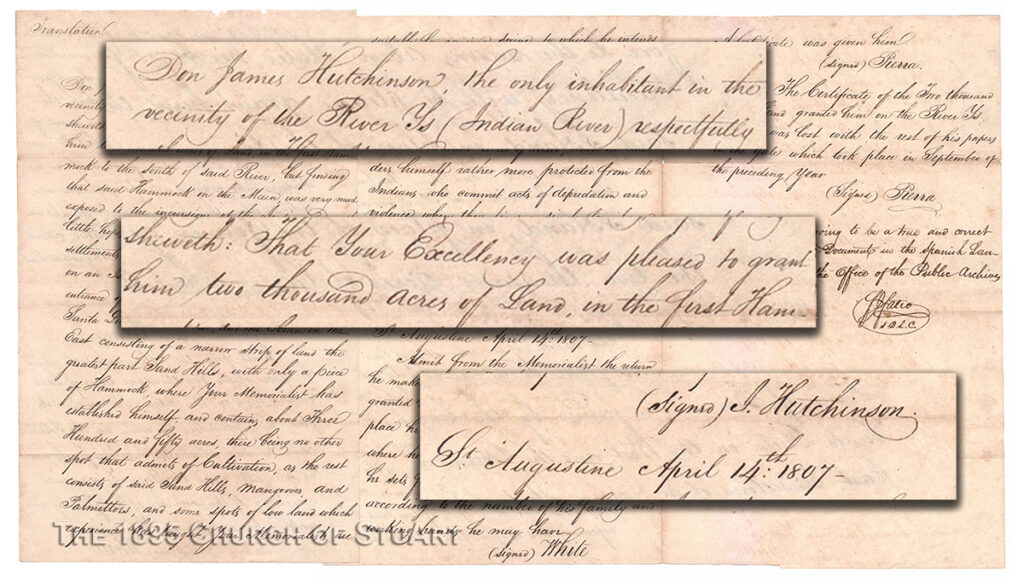

James A. Hutchinson, a Georgian slave owner, came to St. Augustine in March of 1803 and petitioned the Florida Spanish Governor for 2,000 acres on mainland. It was granted and located on the east between Indian River Inlet, and Jupiter Inlet, where Indian River and St. Lucie merge.

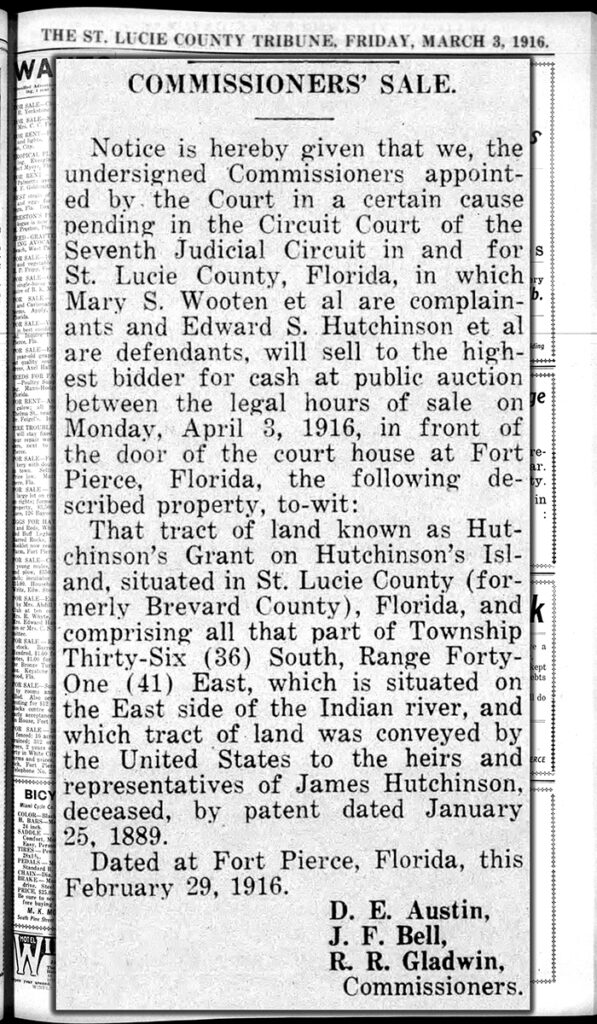

Four years later Hutchinson returned to St. Augustine to say the Indians were molesting his slaves, destroying his crops and stealing his cattle. He requested that his grant be changed to island. This was granted and the present location of the Island is between Fort Pierce and Stuart. in 1809 Hutchinson complained that his plantation had been raided by pirates. The buildings were burned, slaves stolen, crops damaged. Hutchinson returned to St. Augustine to make a complaint and lost his life in a storm on his return trip to the Island. The family returned to Georgia, retaining ownership of the barrier island, but attempted through the years to settle the uninhabited region with no real success. As a result of the Adams-Onís (or Transcontinental) Treaty, signed on February 22, 1819, the two Spanish colonies of East and West Florida were transferred from Spain to the United States and became a single American territory. In 1827, the Congress of the United States confirmed the Spanish land grant as follows: “an island 2,000 acres on the East Coast of Florida running south from the mouth of Indian River to Jupiter Inlet.” This was disputed by the heirs. The government survey showed the island as having more than 2,000 acres. In 1843 John Hutchinson, grandson of James A. Hutchinson, arrived from Augusta, Ga., with the Armed Occupation Act (Indian River Colony) and established residence six miles south of Fort Pierce on the river shore of the island. He was not heard from after the failure of the Indian River Colony in 1849. By about 1900, descendant Edward B. ‘Ned’ Hutchinson had made a permanent home in that remote wilderness of Hutchinson Island, where he had a bean farm.

Gilbert’s Bar2

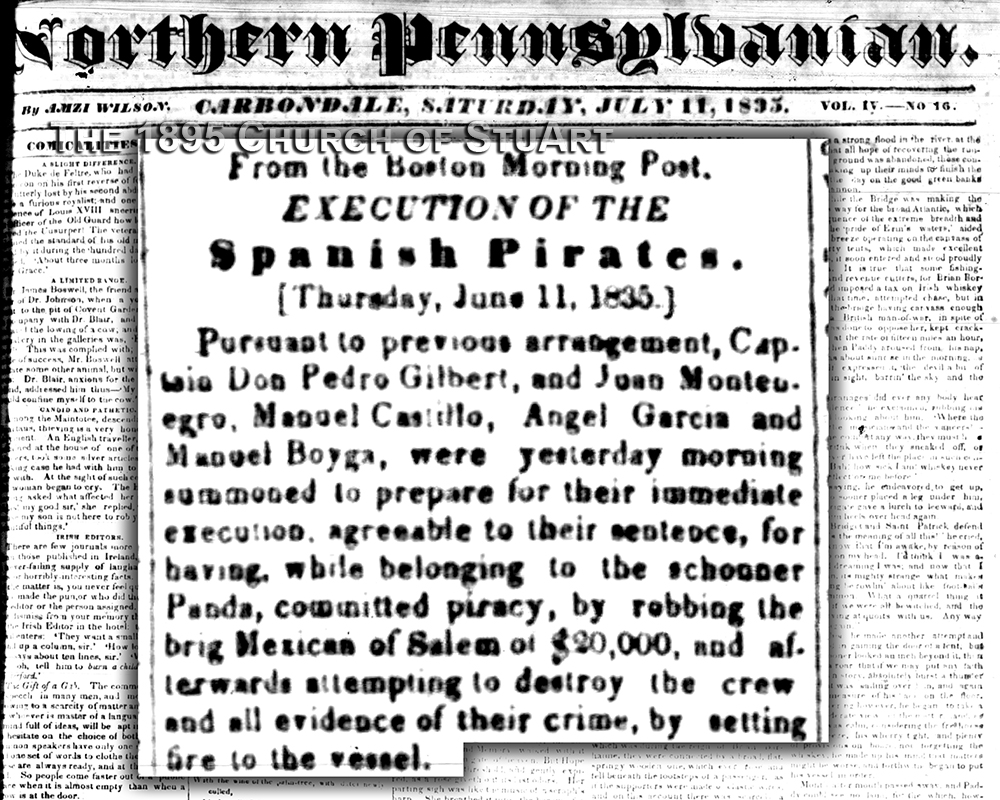

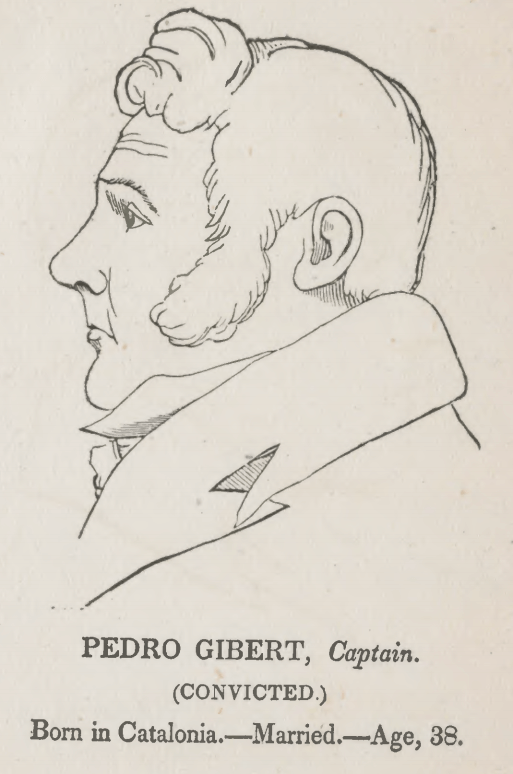

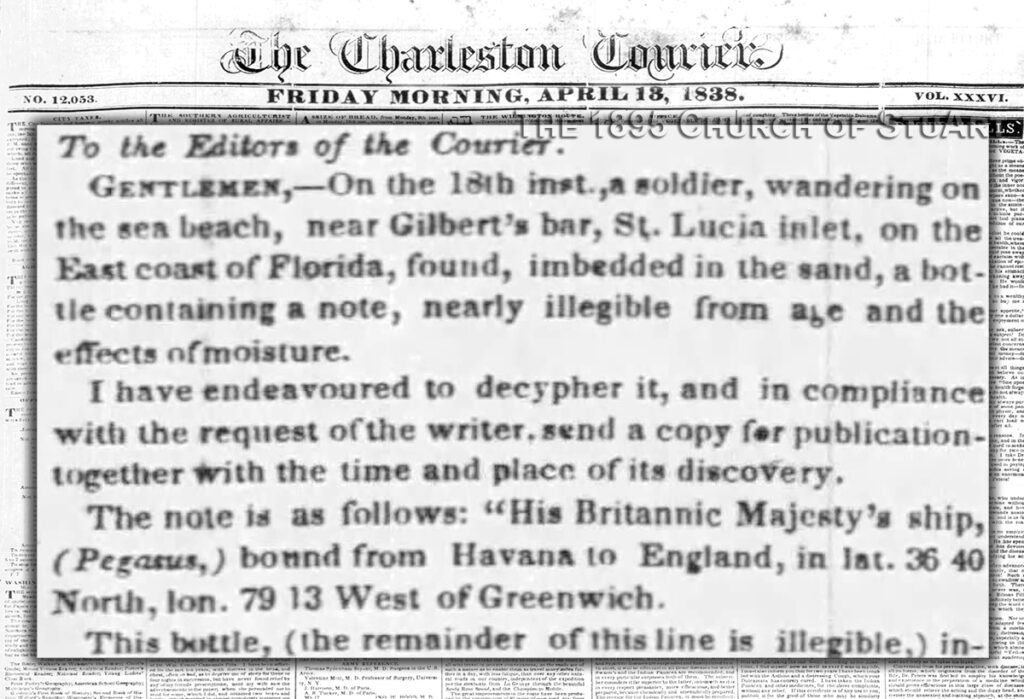

In the late 1820s and early 1830s, Spanish pirate and slave trader Don Pedro Gilbert sailed along the Treasure Coast robbing merchant ships. He used the St. Lucie Inlet to hide his ship from authorities. Gilbert and most of his crew were finally caught by the British Navy off the coast of Africa and returned to the United States for trial in a maritime court in Boston. They were found guilty and executed in 1835. The name “Gilbert’s Bar” began appearing on maps.

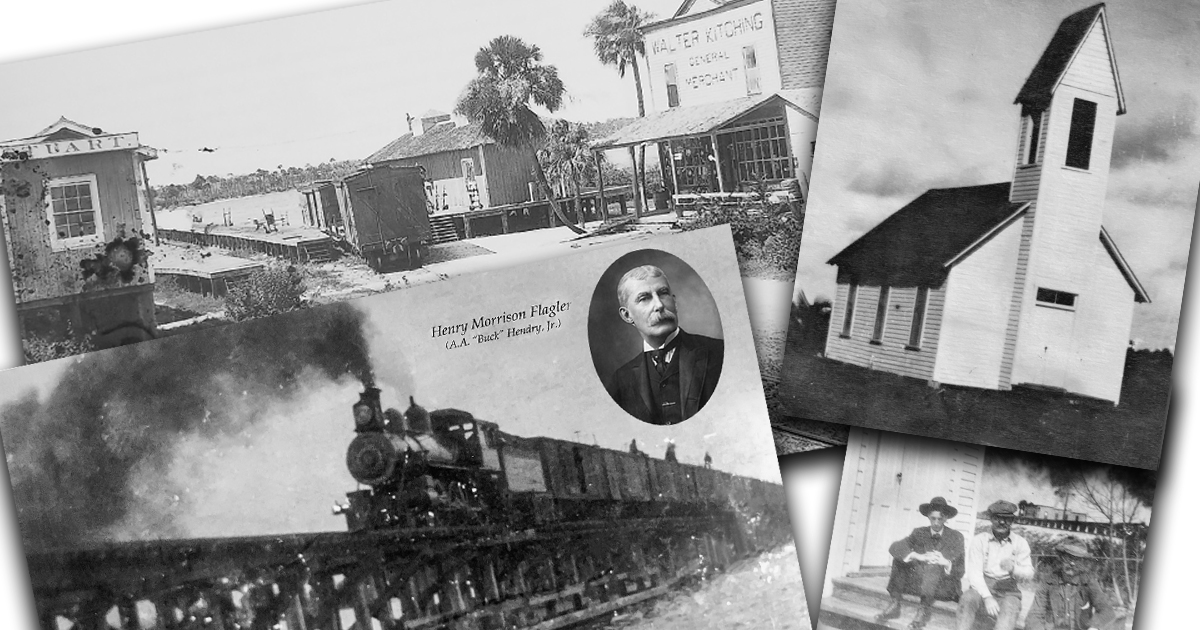

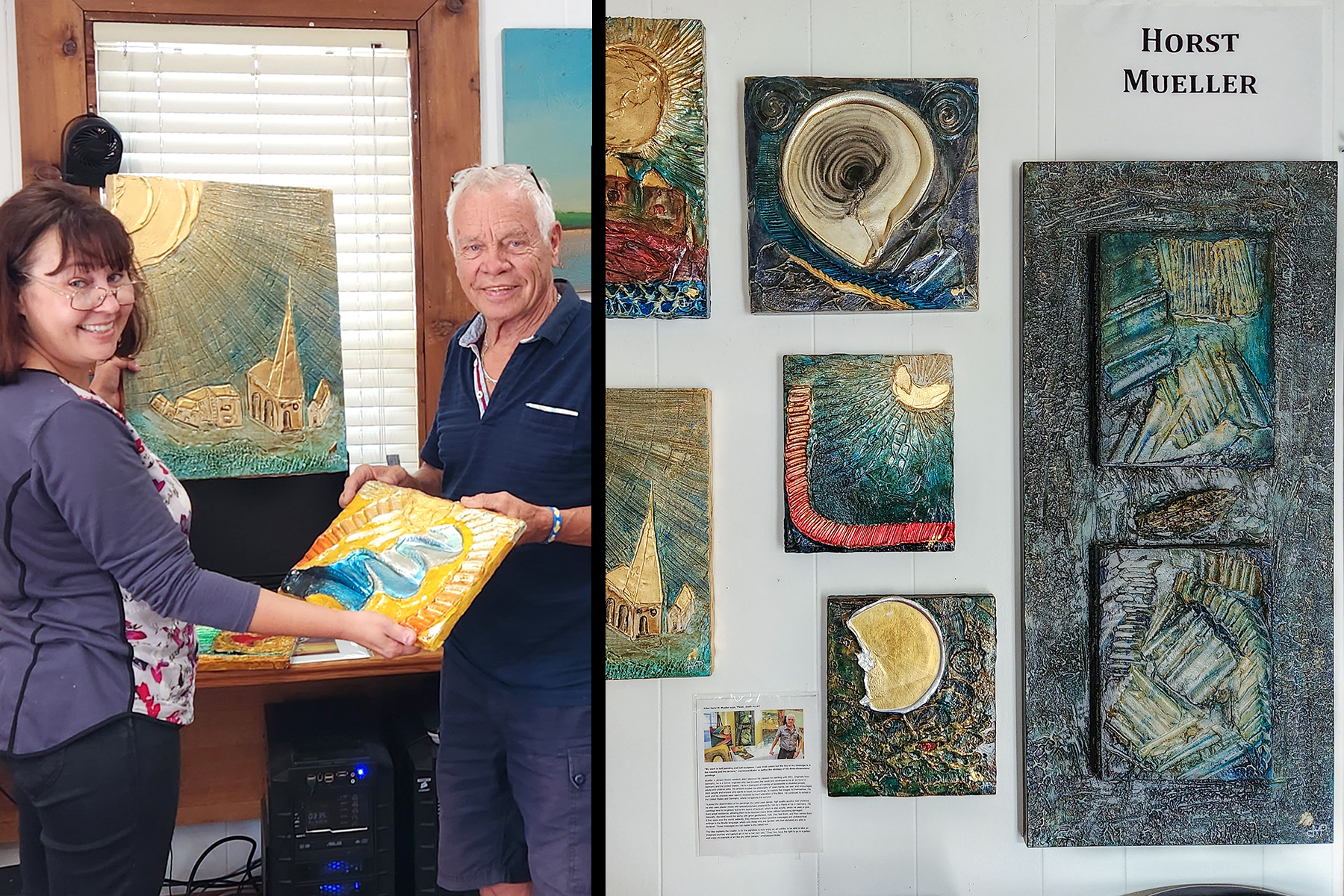

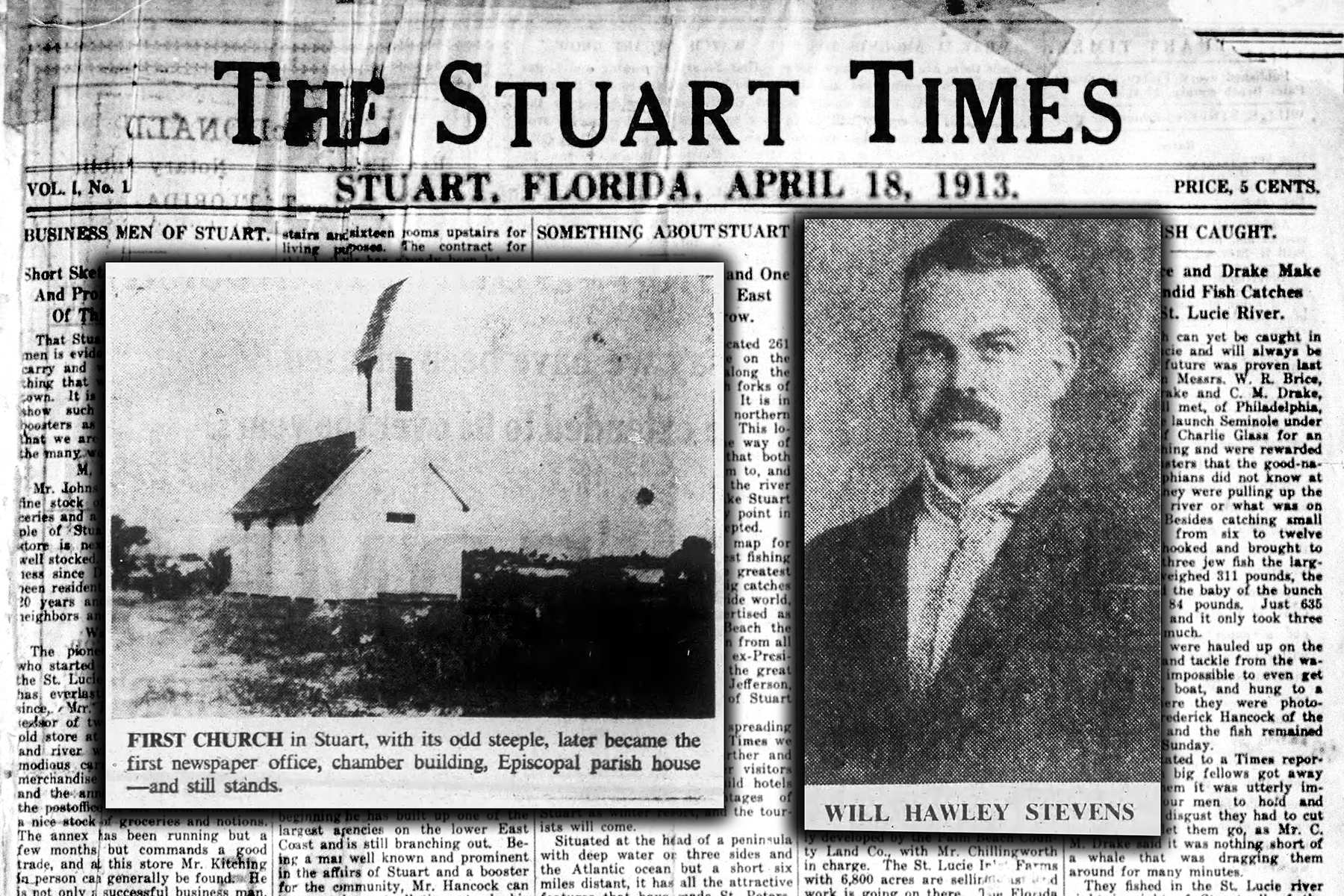

The 1895 Church of StuArt is a historical building of the first community church, also known as the Pioneer Church (the oldest church building in Martin County), built in Stuart in 1895! Your donations help us maintain, restore, and preserve the building, and also continue our research and share historical information and articles. We greatly appreciate your support! The donations are not tax deductible.